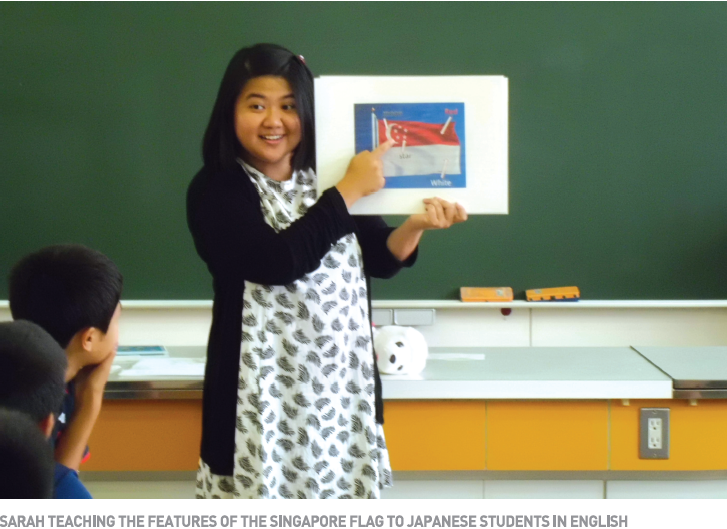

Growing up, I had two big dreams I wanted to achieve in life. The first was to earn a higher degree. The second: to live in Japan for a while. So after completing my Master’s degree, I embarked on the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Programme, a government initiative aimed at increasing grassroots international exchange and English fluency by hiring native English speakers to work as Assistant Language Teachers (ALT) and Coordinators for International Relations all across Japan. I work in a mid-sized junior high school in Yamagata City, Japan as an ALT, where I help Japanese teachers teach English.

I am now in my second year of being their ALT. There is a week to go before my fifteen-year-old students sit for their juken, the high school entrance exams. On days where they have English classes with me, we practice composition and reading comprehension questions from previous juken. It is class time, and I sit at the back of the class, waiting for the kids to come and get their writing checked. The kids are silent, working in intense concentration on the respective tasks set by their Japanese teacher of English, who is quietly working away at the front of the classroom. The atmosphere in the classroom is still, until one boy gets up, grabs his paper and slides into the empty desk next to me.

He gestures helplessly across the A3 sheet and quietly says, “Sarah, I don’t understand any of this. Can you help me?” Two years ago, I would have directed him to his Japanese teacher of English but today I simply lean over and begin explaining the comprehension passage as best as I could.

For an ALT, I had more experience than most of the people who come on the JET Programme. It was not my first teaching job. I taught remedial H2 Literature to failing students at a junior college on weekends. I went on the Ministry of Education’s Internship Programme twice in university to teach English in secondary schools. I was also a Teaching Assistant for a year while pursuing graduate studies.

So, I know how to teach, but only in English, and that counted for exactly nothing when I first stepped into this junior high school in a tiny little city up in the north of Japan. Second-language instruction in Japan is vastly different from how we teach Mother Tongue languages in Singapore. Because of our bilingual policy, students start learning their second language at a very young age and classes are held entirely in that language. However, bilingualism is not as much of a priority here as it is in Singapore, so English lessons only properly start in the third grade of elementary school. By then, it is almost impossible to conduct the class entirely in English.

A MOUNTAIN TO OVERCOME

When I first came to the school in August 2017, the students were still on their summer break. So, the first task I was assigned to was training two fifteen-year-old boys for a city-wide English speech contest. Their Japanese teacher of English greeted me and said, “We heard from your predecessor that you’ve studied theatre, so you should be good at this?” Wanting to be positive on my first day on the job, I smiled brightly and said, “I should be!” But quickly, we realised that I was not.

I knew what to correct. He should emote more here, or go slower there, and join those two words together rather than saying them in a staccato. But to communicate these corrections was a whole different story. My Japanese vocabulary was not extensive enough to say all the things I wanted to. On top of that, I could not understand his questions. So, we always had to have a teacher to translate for us, making practices tedious and frustrating. With the end of the summer break quickly approaching, I began to fear that I was going to be terrible at the job.

This fear compounded when the school term began. Slowly, I was given more responsibilities; the biggest one being English composition. The school had a system where any original sentences composed by students had to be checked by me, so my days were quickly filled with kids accosting me in hallways with their workbooks and worksheets to get their writing marked.

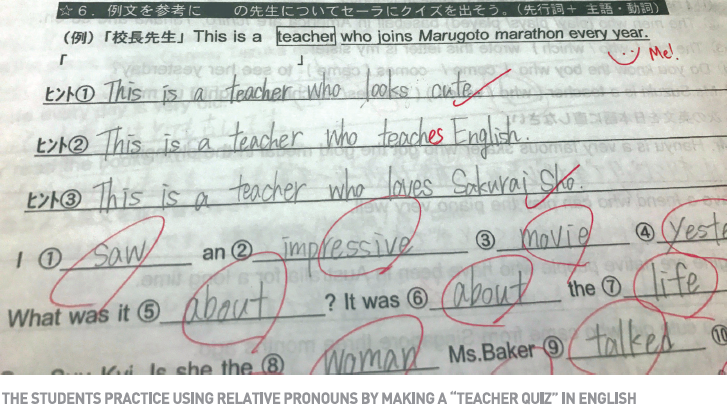

However, I did not want to just correct the sentences. I wanted to guide the kids to the right answer. I wanted them to realise, on their own, that plural nouns required an –s not because their ALT said it had to be there, but because of the grammar rules they had already learnt. But again, I did not have the Japanese vocabulary to prompt them into making the corrections independently. And more worryingly, it became increasingly clear to me that as a native speaker, I had a tenuous grasp of complex grammar rules. So while I could say, “Hey, this is in past tense, so what should you add?” easily enough, saying “This sentence is in passive voice; so what’s the past participle for write?” was beyond me.

Despite my inadequacies, my school was incredibly warm and accepting. Both my students and colleagues would try their best to have conversations with me by using what little English they knew. Kids would start conversations by asking if I had a favourite WWE wrestler, what my favourite Disneyland ride was, and once, my opinion on the Pakistani activist, Malala Yousafzai. In the staffroom, teachers would ask if I was adapting to the unexpectedly severe winter and offer tips for my first attempt at skiing. I tried my best to respond with the limited Japanese I had, and somehow we would meet in the middle.

Forging all these relationships within the school made me want to work harder and become better so I could be the ALT they deserve. So, I studied. If the teacher was teaching grammar, I would pay attention and write things down on my palm. When students received notes on the grammar point in a chapter, I would grab an extra copy and make an English set for myself later. Once I understood the grammar points that were taught in class and had memorised the terms in Japanese, I started using the phrases while checking their writing.

Gradually, it became much easier to nudge the kids into correcting their own writing. When they missed the –s on their third person singular verbs, a quick “Sanninsho tansuu genzaikei!”1 would have them dutifully adding it in. If they wrote, “He is play volleyball”, I could say, “Genzai shinkoukei!”2 and they would slap their foreheads and go, “AH!! I-N-G!”.

The turning point came in November 2017, a day before the students sat for their term tests. I was in the Science Laboratory after school helping a student with his essay on Andres Iniesta, when one of my students – from the summer’s speech contest practice sessions – walked in. He pointed at a sentence in his worksheet and asked for an explanation of the grammar used in it. I was floored. He had first-hand experience with the disaster that I was. He had watched me fumble my words, blank out mid-sentence, and completely crash and burn at being an ALT, but there he was with a question and full belief that I would be able to answer it.

I was beginning to feel more confident. The next time the English speech contest came around, I was flying solo. The Japanese Teacher of English would come for a few practices, but the two new students mostly worked with just me. Miscommunication would still happen, like the time I tried to explain plosive consonant sounds by calling it “bomb-like pronunciation”. Even though my occasional mistakes would send the kids into fits of unstoppable laughter, practices went much better because I knew how to say “Longer pause!”, “Slow down!”, and “Please don’t sound so excited; your speech is about child labour!” in Japanese. I could use these phrases to guide the students better, so when they both won a prize at the competition, it felt that much more rewarding.

Back in the classroom, my fifteen-year-old has finished the comprehension section. He looks at the next question on his juken practice: “The dinner was [cooked/cooking] by my mother.” The student, who had earlier gestured in confusion at his paper, writes c-o-o-k, and then stops, his pencil hovering in hesitance. I whisper, “Ukemi dakara, kakobunshi wo tsukatte kudasai!3” He adds an –ed and smiles. And it is this smile, this smile of self-confidence and satisfaction, which makes me feel like I am slowly becoming the teacher I knew I could be again. ⬛

1 Third-person singular tense

2 Present continuous tense

3 “It’s passive, so use a past participle!”

Siti Sarah Daud is currently living her dream as an Assistant Language Teacher in Yamagata City, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. She also received the MENDAKI Award of Excellence in 2015 and earn a Master of Arts in English at Nanyang Technological University in 2018.